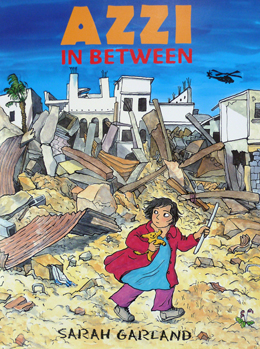

Reviews for Azzi in Between

“It is unusual to come across a picture book that one feels so strongly about that one wants everyone - whatever their age - to read it. There could be o better way of introducing children to what it is like to be a refugee child in Britain than Azzi in Between by Sarah Garland ... one of the most involving stories I have read in a while. Garland treats her subject with unpatronising, well-informed sensitivity ....”

The Observer

“Garland's uncommonly sympathetic eye has tended, until now, to focus on slightly shambolic middle-class English families. But this tremendous book - her best ever - is about a refugee child who comes to England. Her drawings of Azzi's whitewashed home and its palm trees in a war-torn land and of the spartan English hostel in which her family fetches up are assured and well informed. We witness Azzi's alienation at primary school. We feel for her demoralised father who is not allowed to work in this country And we rejoice as family life improves. Moving, involving and without a whiff of condescension - a little masterpiece.”

Kate Kellaway at guardian.co.uk

“...This is a story full of powerful emotions about fear, separation and loss, but it is also a story about hope and new beginnings....Visually this picture book is a tour de force. Garland's expressive line quivers with tension and her subtle use of dark colours and shadow conveys the moments of fear and drama as the family escapes. The movement of the narrative is punctuated by her skilful use of cartoon strips with fast sequences of small frames followed by larger ones that help to convey moments of exhaustion, depression and despair as the family struggle to find their feet in a new country. And yet this is not a sad book - it is also full of warmth and love both within Azzi's family and from those who help them ...”

Rosemary Stones. Editor's choice in Books for Keeps

“Told from a child's perspective, Azzi in Between is a sensitively told story about Azzi and her family who are forced to flee their country to survive. Their country is not named and nor is her family's destination mentioned. This opens the book up to readers that may have experienced forced immigration and can enable them to identify with the family thus helping them to share their stories.

The book has so much potential to be used in educating children and adults ignorant of the privations that refugee families and children experience when fleeing unstable regimes.

Sarah Garland has created a beautiful and moving story about fear, loss and hope that can be read and enjoyed by readers of all ages.”

Teen Librarian

“...a small miracle of compassionate storytelling... Azzi in Between should find its way into every primary class.” Amanda Craig, The Times.

“...This is a moving story not only of survival against the odds, but of the humbling resilience and transcendence of the human spirit. Every school should have several copies.” Picture Book Special for June/July. Jill Bennett's Red Reading Hub.

“...With striking illustrations and beautiful ending, this is an inspiring book for readers eight-plus.” Mary Arrigan, Irish Examiner.

“This is a perfectly wonderful story, and a very necessary one … Opting to make her story a 'comic' means that Sarah gets the message across of what was, what happened then, and the final result, in a way you wouldn't with a traditional novel...” Ann Giles, Bookwitch.

How Azzi Began

For many years, while I had been writing and illustrating picture books set in the familiar territory of home and school, images of displaced children kept returning to my mind. They were the result of stories – often horrific stories – that had been told to my sister-in-law by refugee children, when she had worked with them as a teacher's aid in Oxford schools.

She had shown me their accounts, and I had looked at their childish pictures of guns and helicopters and dead people. They struck my heart. But how could I help? What could I do? I lived in the country, had four young children and worked full time. Then, in the autumn of 2010, our children grown, I travelled to New Zealand with my husband, to spend four months in a small city there. He was to work in a pottery, and I had decided to work on an adult book about a family of early New Zealand settlers, for which I had done some research.

We rented a 'unit', and, on our first day, I walked down the hill to a charity shop, to buy a blanket and lampshade, to make our room homely. It was there that I encountered my first refugee family. They were Burmese, the parents looking through hangars of clothes, the children standing quietly by. They looked anxious, serious and grave.

I walked on, to the library, to collect my reference books, and passed more Burmese families. The children kept close to their parents and they all kept their eyes fixed to the pavement, a contrast to the cheery shoppers and holidaymakers in the streets. At the library – large, thriving and packed with books – I veered off course to the children's section and found a librarian.

“Have you any books you would give to a newly arrived refugee child, that would have any relevance to their situation?” I asked. “Or a book for a New Zealand child that would give them any idea of what experiences a refugee child might have been through, and what they are facing here?”

The librarian paced among the shelves, looking thoughtfully at the titles.

“Do you know? I don't believe I have.”

I walked home. My original project was forgotten. I was filled with a sense of purpose and could think of nothing now but my new idea.

For the rest of our four months in the city I worked on the book. I began by reading memoirs of those who had been forced to flee their homes as children – haunting stories of suffering and endurance. However diverse their nationalities and situations, the stories had common themes – the sudden removal from home, the loss of possessions, the loss of family and friends, the often frightening journey, the privations. Then the arrival, the adjustment to an alien culture and language. Sometimes there was an almost crippling sense of loss of status and of feelings of selfworth, particularly among the men of the family. I found that these same themes were repeated again in government research papers and reports.

A friend was acting as sponsor for one of the 350 – mostly Burmese - refugee families in the city, and she introduced me to several mothers and their children. The rooms in their small houses were very sparsely furnished, but there was always a chest, and in it there were handwoven blankets and clothes from their villages, bright, beautiful things, that they laid out for us to see. This is where

Grandma's blanket in my book sprang from.

My focus became the local school, and the teacher of refugee children there. This was an inspirational place, and she was an inspirational woman. I sat with the new arrivals, with their guarded expressions, their body language showing their bewilderment and anxiety. They had a Burmese helper and translator, who, like them, had spent many years in camps in Thailand, waiting for a chance to leave and make a new life. All of them had had to escape through the jungle and cross the border secretly to reach the camps.

I saw how those children changed as they discovered new confidence, how their eyes brightened, how they began to join in the games and lessons. They painted (helicopter gunships were a favourite subject), and sang, and at the end of term they took part in a gigantic musical which involved everyone in the school and was wonderful. The pride of the parents was also wonderful to see.

In addition to the city library, I was given the run of the E.S.O.L. library and the library at the local technical college, where the adult refugees were taught English, and given encouragement and help wherever I went. That was one of the good things about working on the book – for the first time in my life I worked steadily with other people, knowledgeable and dedicated people. I also

worked with my husband – the first time I had worked with him on a project. The story of Azzi was very much a joint effort.

When we returned to England, I began work on the illustrations. I decided to make Azzi's family of Persian origin, and for their home to be in an unnamed country. I also decided to give the book the format of a graphic novel, in order for it to appeal to as wide an age range as possible. This turned out to be an unexpected pleasure for me, as the book needed to have strong colours and bold

images, and I discovered artist's felt tip pens, concentrated water colours and inks, a big change from my usual method of working. The format also gave me the freedom to speed up and slow down the action visually, For example I could encompass the long journeys of Grandma and Sabeen in one page each of strip cartoons, without interfering with the flow of the book.

In England I was immediately given support by my publishers. I kept re-writing, and was given advice from specialists in immigration law and human rights, from teachers, and from the sister-inlaw who had put the images of those refugee children into my head so many years ago. I also rewrote to make sure the story held to a path that did not include actual horrors, but was nevertheless true.

As for the character of Azzi herself, she developed from a little Jewish girl in a memoir I had read, from a child in that New Zealand school, and a photograph in a newspaper of a Kurdish refugee, which I pinned above my drawing board. But, in the end, she took on a life of her own, a life that she handled with courage, humour, and fortitude.